10 min read

SSI Essentials: Zero Knowledge Proof (ZKP) and Selective Disclosure, till death do us part?

January 23, 2022

Zero Knowledge Proof (ZKP) is a protocol that enables one party to prove a statement to another party by only revealing that the statement is true and leaking no other information.

It has a variety of use cases, but for this article, we will be focusing on the Selective Disclosure use case. For context, Selective Disclosure is "the ability of an individual to granularly decide what information to share" (W3C).

For example, an individual trying to prove they are overage to enter a bar, rather than sharing all the information in their ID card such as name, surname, and address, only sharing their date of birth.

Many claim ZKP is inherent for true privacy-preserving Self-Sovereign Identity technology. However, although we are working towards making Selective Disclosure a reality and the norm, the truth is that current solutions based on ZKP protocols still need to achieve their full potential.

This article analyzes the basics of Selective Disclosure and the most popular methods SSI providers explore using ZKP and alternative protocols.

Zero Knowledge Proof (ZKP) for Verifiable Credentials

In the context of Self-Sovereign Identity, Verifiable Credentials (VCs) are the best way to implement Selective Disclosure. As a refresher, VCs are the digitized, standardized, encrypted versions of your traditional identity documents, including passports, academic records, vaccination cards, or marriage certificates.

The standard Verifiable Credential is a multi-claim credential; that is, one that contains multiple claims (or attributes). For instance, a Verifiable Credential representing a Driver's License includes several claims: Full Name, ID Number, Date of Birth, Street Address, Zip Code, City, and more.

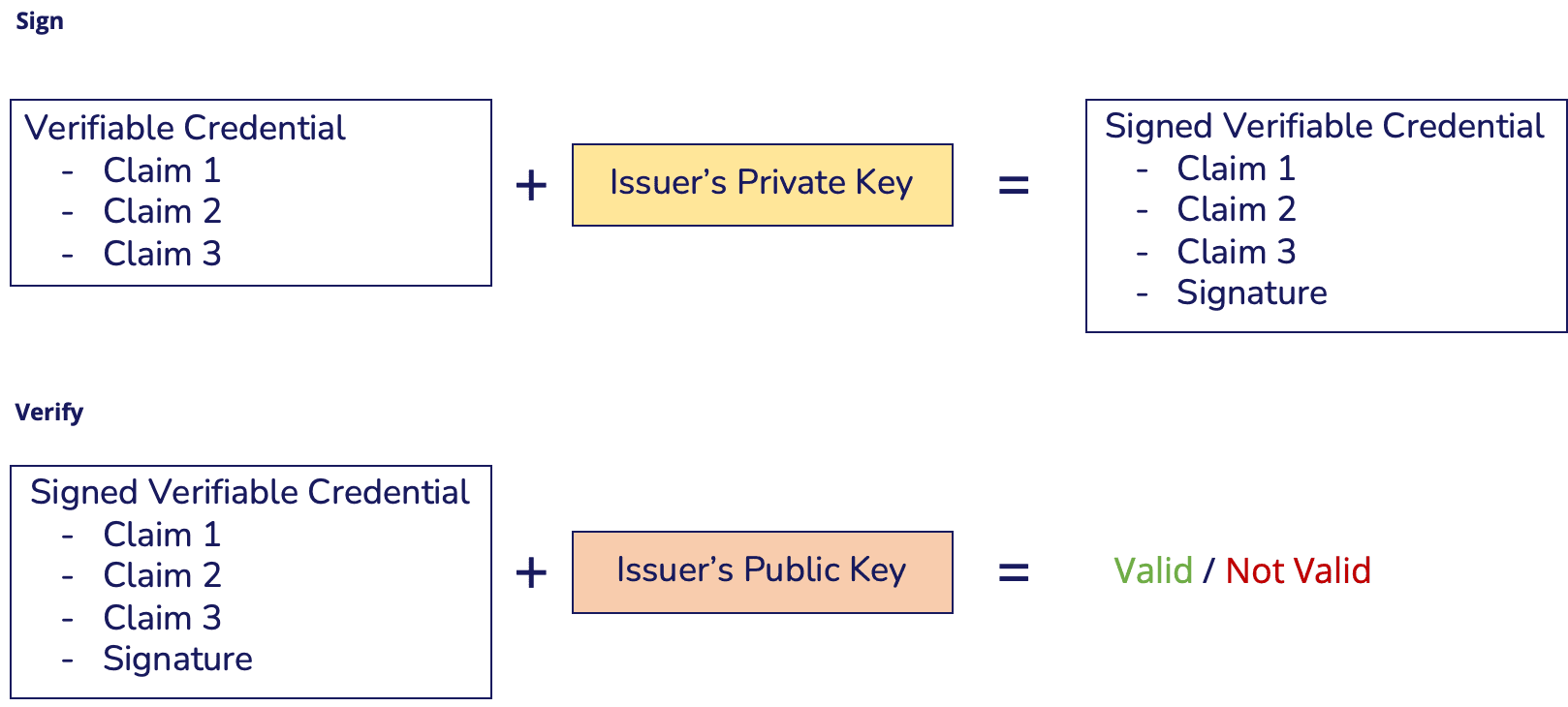

Due to their cryptographically signed nature, a VC can be automatically verified by entities (verifiers) that wish to confirm that you are whom you claim to be online. This is based on standard cryptographic signature schemes.

In a standard VC signature scheme, issuers sign the VC with their private key and produce a signature, proof that is included in the VC. Conversely, a verifier uses the Issuer's public key to prove the signature is valid.

When receiving a VC, verifiers have access to the claims it contains and to the signature made by the credential Issuer. But why should a verifier have access to all the claims in a VC if it only requires one for verification?

Following our previous example, why does a bouncer at a bar have access to the user's address in their ID card if he only needs to read the birthdate? Is there a way to prove a user is overage without disclosing their birthdate?

This is the primary thought behind Selective Disclosure: no information should be shared beyond what is necessary to execute a transaction.

Next up, we will be diving into the recently most popular approach to Selective Disclosure, SD-JWT, as well as other ZKP methods:

- Selective Disclosure for JWTs (SD-JWT)

- Selective Disclosure via Monoclaim Credentials

- Selective Disclosure via BBS+ Signatures

- Selective Disclosure Predicates

- zk-SNARKs (non-SSI)

Selective Disclosure for JWTs (SD-JWT)

Selective Disclosure for JSON Web Tokens (SD-JWTs) is a mechanism that allows a user to selectively disclose the contents of a JSON Web Token (JWT) to a service provider/verifier without revealing all of the information contained within the JWT.

Due to its simplicity, SD-JWT has quickly gained traction, with several implementations and ongoing adoption as an important building block in the latest EUDI Wallet Architecture and Reference Framework.

But let's start from the beginning. A JWT is a compact and secure way to transfer claims between parties. It consists of a header, payload, and signature. The payload holds authenticated user information, such as their identity or authorization.

When a JWT is signed, its contents are protected against modification, but anyone who receives the JWT can read all the information it contains. However, there are instances where users may want to keep certain information private from specific recipients.

SD-JWT enables users to share only a chosen subset of claims within the JWT. This is achieved through additional components.

When a JWT is issued, the issuer sends an SD-JWT to the holder, accompanied by an SD-JWT Salt/Value Container (SVC). The SVC is a JSON object that maps the actual claim values in the SD-JWT to corresponding salts (random data). These salts safeguard the claim values during disclosure.

To selectively disclose specific claims to a verifier, the holder creates an SD-JWT Release (SD-JWT-R) and sends it alongside the SD-JWT. The SD-JWT-R exclusively contains the disclosed claim values.

To verify these claims, the verifier employs the salts from the SD-JWT-R to compute hash digests and compare them to the original SD-JWT.

Selective Disclosure via Monoclaim Credentials

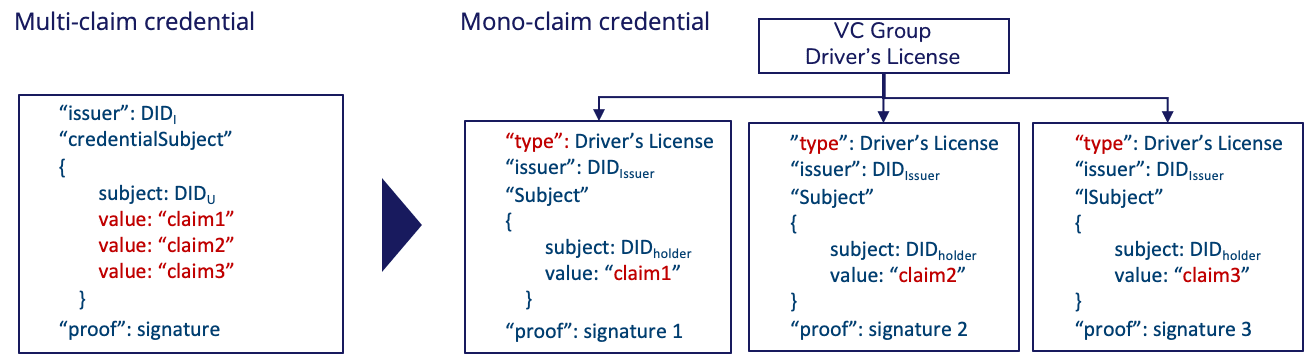

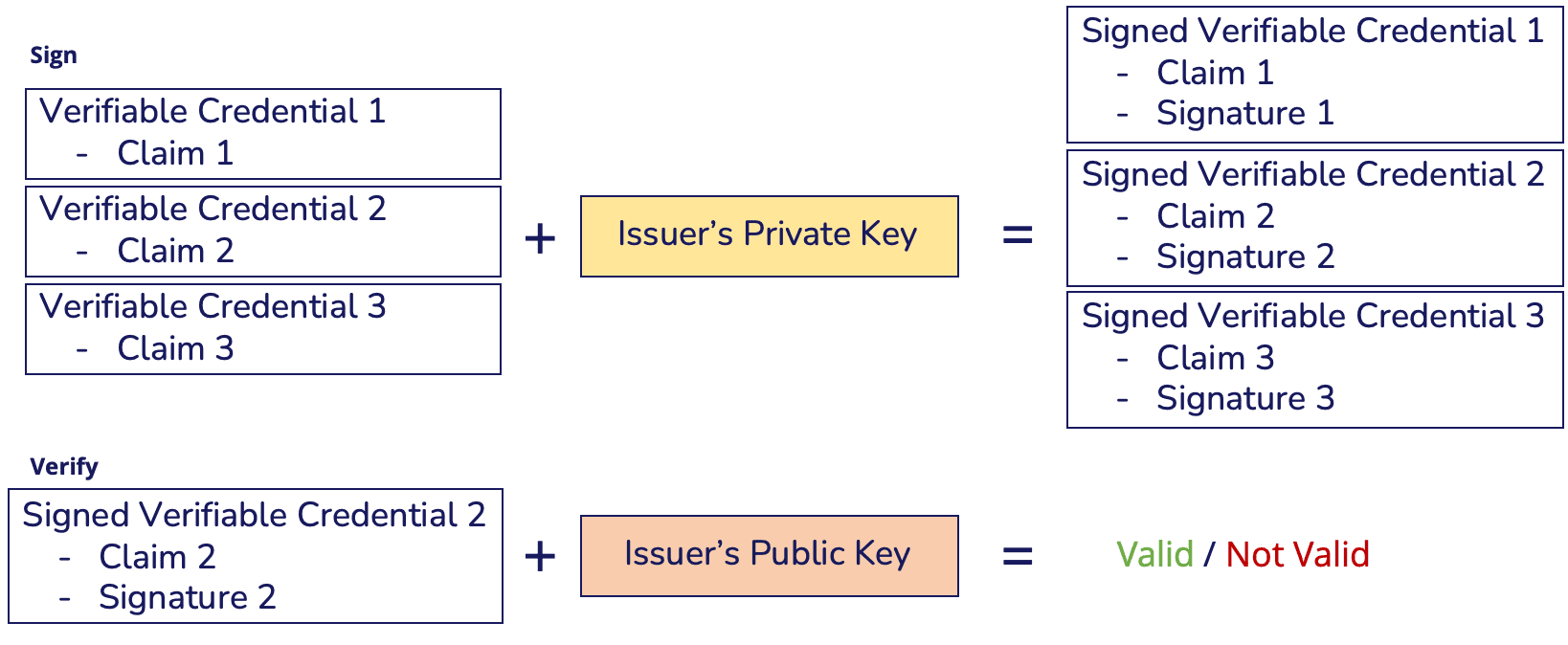

Monoclaim credentials are a selective disclosure method in which a multi-claim credential is divided into a subset of mono-claim credentials, each containing one single claim with an associated cryptographic proof.

For example, the VC representing a Driver's License would be technically divided into a subset of 6 monoclaim VCs, one per claim contained in a Driver's License.The Issuer then individually signs each claim. This technical split is seamless to the user, as the subset is grouped and visually presented as one single VC in their Wallet.

As a result, the user can reveal and confirm specific claims of a VC group by sharing only one of the monoclaim VCs that conform to the group, following standard cryptographic signature processes:

Note that this approach is compatible with multi-claim credentials since a Credential Group could be composed of monoclaim and multi-claim credentials. The only caveat is that the claims contained in multi-claim credentials could not be selectively disclosed.

This feature is helpful for two reasons:

- To implement selective disclosure while keeping compatibility with existing schemas and frameworks that do not yet support selective disclosure.

- To enable an Issuer to link claims to avoid sharing them independently (e.g., a driver's license number and its expiration date) while allowing selective Disclosure on other claims.

Nevertheless, while monoclaim VCs offer the introduction of selective Disclosure and zero knowledge proofs (ZKP) in the SSI world, they are not a scalable long-term solution, particularly with complex VC schemas.

If a particular credential schema were to have 40+ data fields, the computational cost to cryptographically separate the claims becomes inefficient.

Selective disclosure via BBS+ signatures

Like monoclaim credentials allow users to share specific claims from a VC, BBS+ Signatures is a multi-message digital signature scheme (named after its creators Boneh, Boyen, and Shacham) that gives users the possibility of sharing VCs with only specific attributes revealed. How does it work?

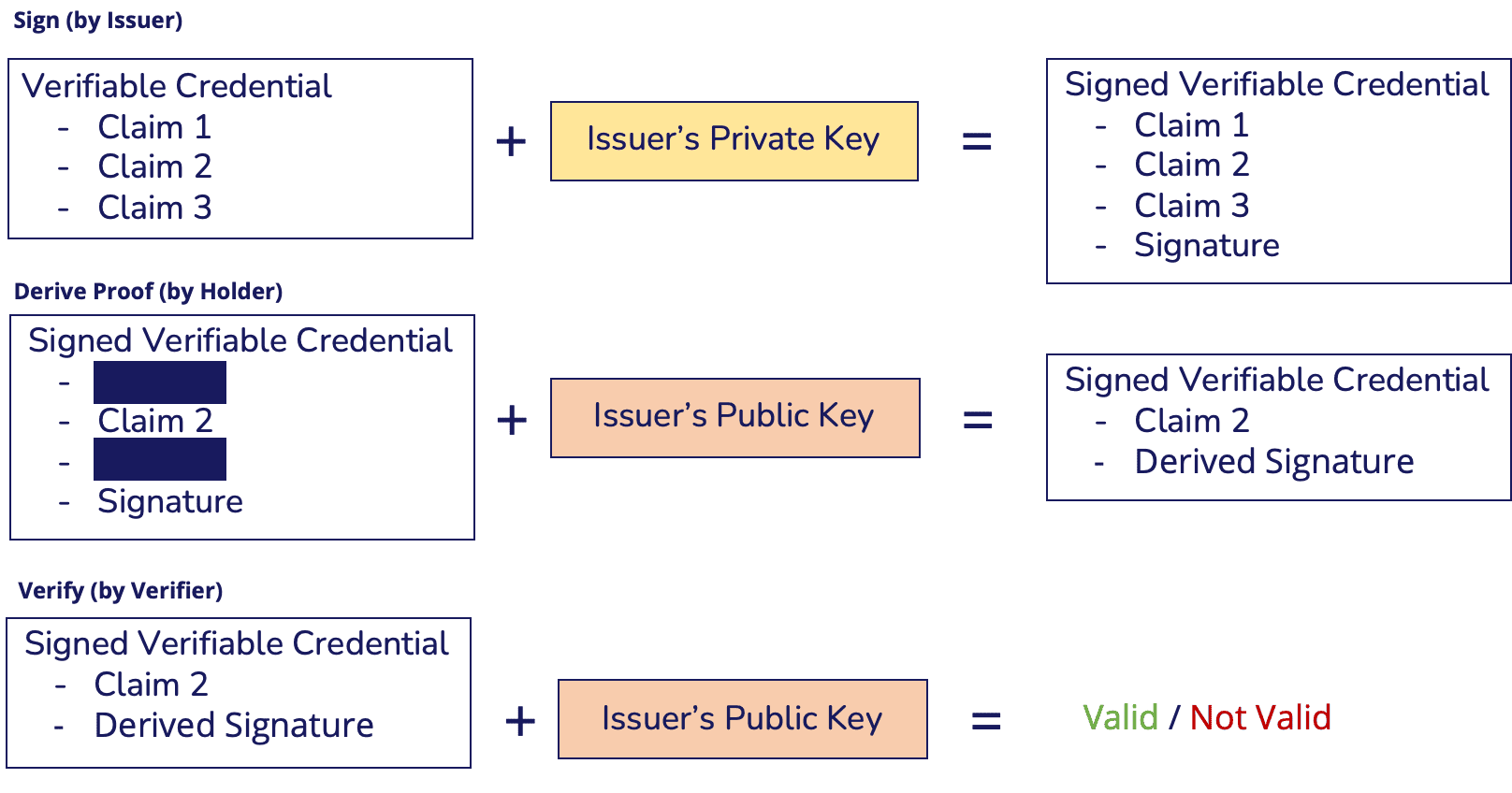

BBS+ signatures allow a VC holder to derive proofs from the original signature:

- Deriving a proof: When a holder takes the signed VC and hides one, several, or none of the containing claims, creating a new signature (a derived proof) using the Issuer's public key. This derived proof can prove that the holder knows all of the original claims contained in the VC but chooses only to reveal the required ones.

- Verifying a proof: The verifier validates the derived proof using the Issuer's public key. This process enables the verifier to confirm the validity of the proof, proving that the subset of claims was part of an original message signed by the Issuer.

Below is an overly-simplified model of how BBS+ signatures work:

An advantage of BBS+ signatures is that they allow a holder to keep the original signature safe, which adds another layer of privacy to verifiable credentials. In turn, holders have complete control to decide when and what must be revealed, removing this power from the signer.

The main downside to BBS+ signature scheme VCs is that it does not support ZKP predicates (explained in the next section). Yet, compared to the monoclaim credential approach, BBS+ signature schemes remain a more scalable choice for Selective Disclosure.

More details on BBS+ signature schemes are below: BBS+ signature scheme: https://mattrglobal.github.io/bbs-signatures-spec/ BBS+ cryptography: https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/663.pdf

Selective Disclosure Predicates

A novel selective disclosure approach that goes beyond hiding non-necessary attributes is the implementation of predicates in the sharing/verification of verifiable credentials.

Predicates allow verifiers to check a value (for example, age) against a certain condition (the subject's age must be greater than 18), successfully limiting the amount of information disclosed (the subject's specific age is never revealed).

The predicate policies are usually set by the verifier who uses it to verify/authenticate its users (let's continue with the previous example of a Bar verifier).

How does it work? Verifiers can create predicate policies and conditions, such as designating ranges (Alice must be over 18) or requesting membership to a specific set (Alice must be a University X student).

Users respond to this policy with FALSE/TRUE values rather than revealing claim values. This is achieved with certain signature types that allow claims from a standard verifiable credential to be presented as predicates.

But the use case goes beyond age verification and can include account balance or credit scores, which is highly sensitive personal data that is often requested by real estate agents when renting/buying a home or by banks when taking out a loan.

The main setback of this approach is that predicate policies in Verifiable Credentials can only be used for limited types of verifications: "greater/smaller than" conditions and for numeric value verification.

SNARKs

Other organizations are exploring alternative ZKP protocols like zk-SNARKs (Succinct Non-interactive Argument of Knowledge).

Like BBS+ signatures schemes, zk-SNARKs cryptographic solution uses proofs but proves the possession of information without revealing the inputs used to obtain the data and requiring no interaction between the holder and verifier.

This is possible by "turning what you want to prove into an equivalent form about knowing a solution to some algebraic equations" (ZCash).

This solution has a tremendous potential impact to give users fast Zero Knowledge interactions with their verifiable credentials. Unfortunately, we have yet to see the application of zk-SNARKs on VCs, as the solution is mainly being pioneered in the crypto world to prove the validity of crypto transactions.

The single yet costly barrier to the construction and application of zk-SNARKs lies in its cryptographic complexity, which makes it computationally expensive.

Why is SD-JWT the preferred method for Selective Disclosure?

Having explored various approaches to selective disclosure, why has been SD-JWT the selected method in the new eIDAS regulation?

The reason is that it offers advantages in terms of ease of implementation, adoption, interoperability, and a standardized format due to its reliance on JWTs and widely-used cryptographic algorithms like digital signatures.

On the other hand, other zkp mechanisms like Monoclaim Credentials, BBS+ signatures, selective disclosure predicates, and zk-SNARKs may provide more specialized capabilities or stronger privacy guarantees in specific use cases but may require more complex implementations and have limited standardization or adoption in comparison.

Samuel Gómez

CTO